Typhoid Fever at Home and Abroad

Outbreaks, Alerts and Hot Topics - March 2023

Column Author and Editor: Chris Day, MD | Pediatric Infectious Diseases; Director, Transplant Infectious Disease Services; Medical Director, Travel Medicine; Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

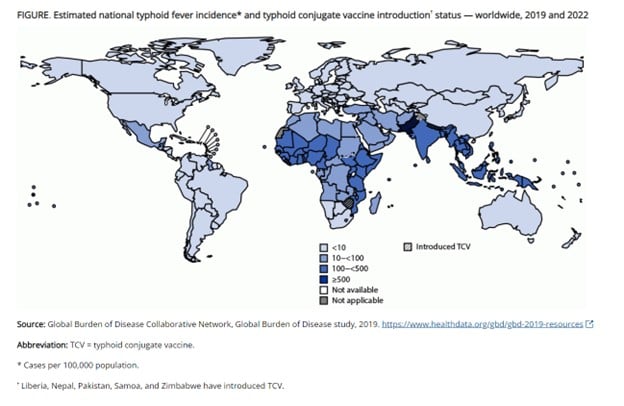

Worldwide, typhoid fever presents a significant health burden with an estimated 11-21 million annual cases and 148,00-161,000 deaths (estimated for 2015), primarily in low- and middle-income countries. The precision of these estimates is limited by several factors including the difficulty of distinguishing typhoid fever from other febrile illnesses and dependence on disparate methods of data-gathering that include both passive surveillance in individual countries and active surveillance in the form of cohort studies. Confirmation of typhoid infection is dependent on laboratory methods, usually blood culture, which has a sensitivity of only 40%-60%. However, blood cultures are often not obtained, and when they are available, pre-treatment with antibiotics is common, further reducing sensitivity.1 Estimates of the burden of infection in different regions are based on models that consider the available data. Consistency among such estimates show that incidence of typhoid is high in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Oceania, but estimates show less agreement on the differences in incidence between these different regions.2

While typhoid fever is typically responsive to directed antibiotic therapy, antibiotic resistance in the causative organism, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (S. Typhi), is increasing in prevalence. Multi-drug resistant (MDR – resistant to chloramphenicol, ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) S. Typhi now comprises around 35% of isolates in Asia and 75% in Africa; strains resistant to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins as well (extensively drug resistant, or XDR) have been found in Pakistan.1

Reduction and perhaps eventual elimination of typhoid fever is potentially achievable in the long term through provision of safe drinking water and improved sanitation and hygiene. Typhoid vaccines appear to have the potential to significantly reduce the burden of infection in endemic populations even while improvements in sanitation are still in progress.3 Two types of typhoid vaccines, both developed in the 1990s, are used in the United States for travelers to endemic regions: an injectable polysaccharide vaccine and an oral live attenuated vaccine. Use of these vaccines in low-resource endemic countries has been limited by poor immunogenicity in young children and infants (the polysaccharide vaccine, like other polysaccharide vaccines, is not useful until around age 2, while the oral vaccine available in the U.S. cannot be given until age 6) and by a limited duration of protection. Redosing of the polysaccharide vaccine is recommended after two (U.S. labeling) to three years (labeling in a number of other countries), while the oral vaccine should be repeated every three to seven years (depending on national labeling). Polysaccharide vaccine, nevertheless, has been used in routine immunization programs in China, Vietnam and India with available data suggesting reductions in typhoid fever cases. More recently, two typhoid conjugate vaccines have been approved in India4,5 and prequalified by the World Health Organization (WHO). Conjugate typhoid vaccines are anticipated to provide more durable immunity with fewer doses (though a booster may eventually prove to be needed, especially in those first vaccinated under age 2) than do older typhoid vaccines.6 A recommendation was issued in 2018 from WHO that typhoid conjugate vaccine introduction should be a priority in countries with a high incidence of typhoid fever or a high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in S. Typhi. These vaccines have now been incorporated with the routine immunization schedule in Liberia, Zimbabwe, Nepal and Samoa (for use at age 9 months) and in Pakistan (for use at age 15-18 months) with more than 75 million children given these vaccines, including older children in catch-up campaigns.1

Travelers to endemic countries from the United States remain at risk of typhoid fever. Prevention, including pre-travel advice on food and beverage safety as well as pre-travel typhoid immunization with the domestically available polysaccharide and oral vaccines, remains important. About 425 people in the United States become ill with typhoid fever every year.7 Enteric fever (including typhoid and paratyphoid fever) accounted for 18% of cases of fever in travelers reported to GeoSentinel between 1996 and 2011.8 Evaluation of fever in the returning traveler, especially those with rash, abdominal pain, normal or low white blood cell counts, or fevers lasting more than two weeks, should include consideration of typhoid fever. Blood cultures should routinely be obtained as part of that evaluation. Because of the inadequate sensitivity of blood cultures, a diagnosis must often be made clinically.

Source of map: Reference 1. All material in the MMWR series is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission.

References:

- Hancuh M, Walldorf J, Minta AA, et al. Typhoid fever surveillance, incidence estimates, and progress toward typhoid conjugate vaccine introduction – worldwide, 2018-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:171-176. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7207a2

- GBD 2017 Typhoid and Paratyphoid Collaborators. The global burden of typhoid and paratyphoid fevers: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;4:369-381.

- Youfsafzai MT, Heywood AE. Typhoid conjugate vaccine: are we heading towards the elimination of typhoid in endemic countries? Lancet Glob Health. 2022;9:e1224-e1225.

- Beran J, Goad J. Routine travel vaccines: hepatitis A and B, typhoid, influenza. In: Keystone JS, Freedman DO, Kozarsky PE, Connor BA, Nothdurft HD, eds. Travel Medicine. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2013:87-100.

- Khan MI, Franco-Paredes C, Sahastrabuddhe S, Ochiai RL, Mogasale V, Gessner BD. Barriers to typhoid fever vaccine access in endemic countries. Res Rep Trop Med. 2017;8:37-44.

- Vashishtha VM, Kalra A. The need & the issues related to new-generation typhoid conjugate vaccines in India. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151(1):22-34.

- Typhoid fever. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID) and Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ). Accessed March 2, 2023. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/typhoid

- Thwaites GE, Day NPJ. Approach to fever in the returning traveler. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:548-560. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmra1508435

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Yellow Book 2020: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press ; 2019. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/yellowbook-home-2020

See all the articles in this month's Link Newsletter

Stay up-to-date on the latest developments and innovations in pediatric care - read the March issue of The Link.