What's the Diagnosis?

October 2022

Visual Diagnosis

Column Author: Ronald Palmen, MD | Internal Medicine - Pediatrics, PGY-3

Column Editor: Joe Julian, MD, MPHTM, FAAP | Hospitalist, Internal Medicine – Pediatrics | Clinical Associate Professor, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

An 11-day-old male presents to the emergency department with his mother for concerns of intermittently increased respiratory rate. He started having some subcostal retractions with increased work of breathing two days prior to evaluation but has otherwise been acting like himself. He was born at 41 weeks’ gestational age via spontaneous vaginal delivery without complications. Mother had appropriate prenatal care and negative group B streptococcal screening. Mother states that the breathing rate becomes fast for approximately 30 minutes, slows down with decreased retractions, then speeds up again after 30 minutes to an hour. He is primarily breastfed and back to birth weight.

In the emergency department, vital signs are as follows: temperature 37.3°C, heart rate 164, respiratory rate 46, and oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. On physical exam, he is arousable and in no distress. His lung exam is clear to auscultation except for slightly diminished aeration at bases. His work of breathing is mildly elevated with subcostal retractions and varying tachypnea from 40 to 70 breaths/minute. The cardiac exam is notable for a regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, and a present S1/S2. Brachial and femoral pulses are 2+.

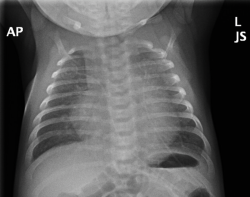

Basic metabolic panel and complete blood counts are within normal limits. Chest X-ray is shown below.

What is the next best step in management of this patient?

A. Administration of intravenous alprostadil

B. Reassurance to mother and discharge with return precautions

C. Outpatient referral to otolaryngology (ENT)

D. Admission for intravenous ceftazidime and ampicillin

Answer: A. Alprostadil administration

This patient is presenting with tachypnea and chest radiograph findings indicative of enlarged cardiac silhouette and pulmonary edema. These findings are consistent with acute heart failure. In this otherwise healthy 11-day-old male, the most likely diagnosis is critical coarctation; therefore A is the correct answer. Alprostadil should be administered to maintain the patency of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Critical coarctation, as seen in this patient above, relies on an open PDA to circumvent the aortic coarctation. When the PDA closes, this restricts forward flow of blood and can result in congestive heart failure and respiratory distress secondary to pulmonary edema. An easy test that can be performed to screen for this condition includes four extremity blood pressures.

If the chest radiograph were normal in appearance, the most likely diagnosis would be periodic breathing. Periodic breathing episodes are characterized by a pattern of alternating breaths and brief respiratory pauses. Although descriptions vary, periodic breathing is usually defined as repetitive cycles of breathing and respiratory pauses that are approximately five to 10 seconds in duration and predominantly happen when the infant is sleeping. In our case, the episodes last much longer than a few seconds and occur when he is awake as well.

Otolaryngology referral is indicated with upper airway anatomical causes of respiratory distress. The most common condition is laryngomalacia, which refers to collapse of the supraglottic structures during inspiration and is the most common congenital anomaly of the larynx. The most common presentation includes noisy breathing, as the collapse can cause inspiratory stridor. This condition typically self-resolves over time as the child grows but may persist in children with underlying neuromuscular or genetic syndromes. Indications for intervention include apnea spells and/or hypoxia.

Finally, although breathing abnormalities in the infant population may indicate infections and signs of sepsis, this patient is described as well appearing, and vitals show no fever. The chest radiograph may be read as infiltrates, but his clinical presentation is not consistent with lung infection.

References:

- Feltes TF, Bacha E, Beekman RH III, et al.; American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Heart Association. Indications for cardiac catheterization and intervention in pediatric cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(22):2607-2652. Published online May 2, 2011. PMID: 21536996. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821b1f10

- Patel M, Mohr M, Lake D, et al. Clinical associations with immature breathing in preterm infants: part 2-periodic breathing. Pediatr Res. 2016;80(1):28-34. Published online May 22, 2016. PMID: 27002984. PMCID: PMC4929034. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.58

- Kay DJ, Goldsmith AJ. Laryngomalacia: a classification system and surgical treatment strategy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85(5):328-336. PMID: 16771027.