What's the Diagnosis?

January 2021

Visual Diagnosis

Co-author: Allison Adam, MD | Pediatric Resident

Co-author: Laura Plencner, MD | Pediatric Hospital Medicine | Associate Professor of Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

Column Editor: Angela Myers, MD, MPH | Director, Division of Infectious Diseases | Professor of Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine | Medical Editor, The Link Newsletter

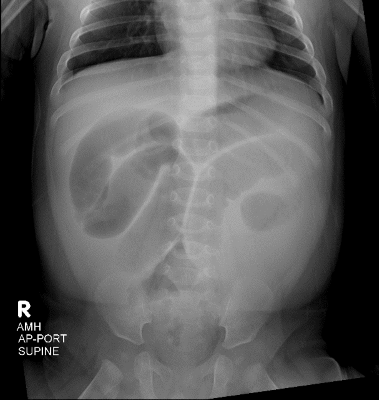

A 5-month-old, previously full-term, otherwise healthy male presents with a one-day history of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis and decreased urine output. He has also had rhinorrhea for four to five days. Mom reports the patient has had five episodes of emesis in the last 24 hours and has not had a wet diaper in 12 hours. The patient has not had a bowel movement in the last 48 hours. Mom states he has not been significantly irritable, but he has been more sleepy than usual. He has been afebrile and has had no recent sick contacts or travel. On examination his abdomen is soft, and bowel sounds are appreciated. He has no hepatosplenomegaly. An abdominal radiograph is obtained.

Of the following, which diagnosis is the MOST likely etiology of the patient’s clinical picture:

A. Constipation

B. Intussusception

C. Pyloric stenosis

D. Viral gastroenteritis

Answer: B. Intussusception

This patient’s radiograph is concerning for possible obstruction, and intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children aged 6 to 36 months. An abdominal ultrasound was performed that confirmed the diagnosis of ileocolic intussusception. The radiograph does not show a stool pattern consistent with constipation, but rather shows dilated loops of small intestine. This would not be consistent with a proximal obstruction such as pyloric stenosis, and viral gastroenteritis would not present with bowel obstruction.

Intussusception is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in young children.1 Over 90% of cases of intussusception occur at the ileocecal junction and are referred to as ileocolic intussusception.1 Approximately one quarter of patients presenting with intussusception have an identifiable “lead point.”1 A lead point is a variation or lesion in the small bowel that gets trapped during peristalsis and pulled into a distal portion of the small bowel, causing the intussusception. The other 75% of cases are idiopathic and no lead point is identified. Meckel’s diverticulum, polyps, small bowel lymphomas and vascular malformations are examples of possible lead points.2 In Henoch-Schönlein Purpura, patients can have small bowel hematomas that can serve as possible lead points.1,2 Approximately 30% of patients with intussusception experience a preceding viral illness, and a strong association has been demonstrated with preceding adenovirus.1,3

The typical presentation of a patient with intussusception is episodes of inconsolability, usually lasting 15-20 minutes. Patients frequently draw their legs up to their abdomens during these fits. The episodes become more frequent and more severe and are almost always associated with vomiting. Half of cases will have frankly bloody stools, and an additional 25% of patients will have a positive hemoccult.1

If the patient is hemodynamically stable and the suspicion for perforation is low, the management is reduction with pneumatic or hydrostatic pressure enema. Reduction is most commonly performed with fluoroscopic guidance. “Hydrostatic” enemas use either saline or contrast, and “pneumatic” enemas are performed with air. Ultrasound guidance can be used and is advantageous in its improved detection of pathologic lead points compared to fluoroscopic guidance. Ultrasound guidance also avoids ionizing radiation. These reduction techniques have a success rate of 70-85%. Successful reduction is more common in idiopathic causes of intussusception compared to those with lead points. Four percent of patients have recurrence of intussusception within 48 hours, so appropriate return precautions are always necessary.1

References:

- Vo N, Sato TT. Intussusception in Children. (2020). In JI Singer. B Uk Li. (Ed.), UpToDate. Retrieved 12/9/20 from https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.cmh.edu/contents/intussusception-in-children?search=intussusception&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~119&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

- Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, 21st ed., Elsevier, 2018. Acute Abdominal Pain.

- Burnett E, Kabir F, et al. Infectious Etiologies of Intussusception Among Children <2 Years Old in 4 Asian Countries. J Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 7;221(9):1499-1505. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz621. PMID: 31754717; PMCID: PMC7371463.