What's the Diagnosis?

December 2022

Visual Diagnosis

Column Author: Aaron Shaw, MD | Fellow, Infectious Diseases

Column Editor: Joe Julian, MD, MPHTM, FAAP | Hospitalist, Internal Medicine – Pediatrics | Clinical Associate Professor, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

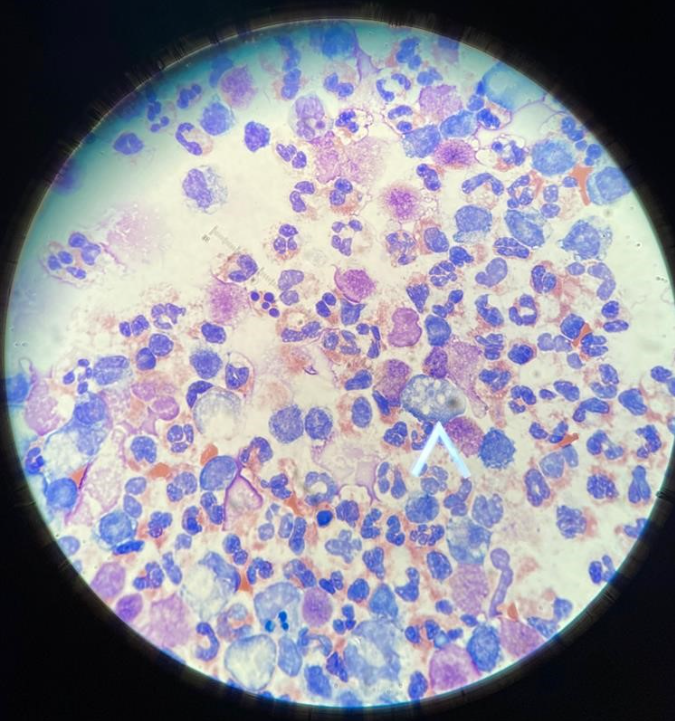

A 4-year-old male presents with two days of fever, headaches and increasing somnolence. On arrival to the hospital, he is actively seizing and requires intubation. Although he is sedated and intubated, his exam is normal. A lumbar puncture is performed, which shows a WBC count of 20,600, RBC of 750, protein of 1200 and glucose of <20. Vancomycin, ceftriaxone and acyclovir are empirically started. Review of the initial Gram stain of the CSF shows no organisms. However, Wright staining of the CSF shows the following image:

Which of the following organisms is most likely responsible for this patient’s presentation?

- Naegleria fowleri

- Rickettsia rickettsii

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Cryptococcus neoformans

Correct answer: A. Naegleria fowleri

The patient in the above vignette has primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a condition caused by the amoeba Naegleria fowleri. The Wright stain shown above illustrates the presence of several trophozoites surrounded by many neutrophils, which confirmed the diagnosis. These organisms were missed on the initial Gram stain, but after they were found on a wet mount slide, they were easily located with the Wright stain. Presence of trophozoites indicates a parasitic infection. Rickettsia rickettsii (cause of Rocky Mountain spotted fever) is an intracellular bacteria that can rarely cause meningoencephalitis, but does not usually appear in the CSF. Tuberculosis meningitis usually has a lymphocytic predominance in the CSF rather than a neutrophilic predominance and is found on acid fast staining. Cryptococcus is a fungus that would also cause a lymphocytic predominance in the CSF and can be visualized using the India ink stain.

PAM is a rapidly progressive and almost always fatal disease. Overall case-fatality rate is estimated between 92% and 98%.1 Symptoms include many of the symptoms seen in bacterial meningitis or viral encephalitis, often with fevers, seizures, altered mental status, headaches and vomiting.1,2 Distinguishing between these different infections can be challenging, as both PAM and bacterial meningitis can have very high WBC counts and protein levels, as well as very low glucose levels. Therefore, it is imperative to obtain information about possible exposures.2 PAM has been associated with recent freshwater exposure (swimming/diving in lakes, Neti pot usage, etc.) in as many as 81% of cases.3 The diagnosis is generally established by finding motile trophozoites when examining a wet mount of CSF and can be confirmed via polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Maintaining a high index of suspicion for PAM is important, as survival hinges on early initiation of appropriate treatment. Guidance on antimicrobial therapy is based on what medications have led to survival in previous cases. At present, the recommended regimen for PAM includes amphotericin B, miltefosine, fluconazole, azithromycin and rifampicin. Amphotericin B is considered the drug of choice, as it has shown the most favorable in vitro activity and has been used in the vast majority of survival cases.1,4 Miltefosine is a recent addition and its use in PAM has been extrapolated from successes in treating leishmaniasis and Balamuthia infection. Fluconazole and azithromycin have demonstrated synergistic activity with amphotericin and have favorable susceptibilities on in vitro testing.

References:

- Gharpure R, Bliton J, Goodman A, Ali IKM, Yoder J, Cope JR. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of primary amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri: a global review. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(1):e19-e27. PMID: 32369575. PMCID: PMC8739754. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa520

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50(1):1-26. PMID: 17428307. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00232.x

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(7):968-975. PMID: 19845995. doi:10.1017/S0950268809991014

- Stowe RC, Pehlivan D, Friederich KE, Lopez MA, DiCarlo SM, Boerwinkle VL. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis in children: a report of two fatal cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;70:75-79. PMID: 28389055. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.02.004