What's the Diagnosis?

April 2022

Visual Diagnosis

Column Editor: Joe Julian, MD, MPHTM, FAAP | Hospitalist, Internal Medicine - Pediatrics | Clinical Associate Professor, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

An 11-month-old female is admitted for fevers and vomiting. The symptoms started seven to eight days ago with cough and rhinorrhea. Over the past three days she has developed non-bloody non-bilious vomiting. She has felt warm during the entire illness course, but no temperatures were checked. She has only had one wet diaper over the past 18 hours. She was seen two days earlier both in urgent care and in the emergency department, where she was discharged with supportive care. Of note, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza testing were negative at that time. She does not attend child care, but there are school-aged children in the home. No associated diarrhea, rash, or current cough or congestion. She had a gastrointestinal illness approximately four weeks prior to this current illness and previously had COVID-19 seven months earlier.

Vital Signs and Physical Exam

Temperature 39.2°C | Heart rate 168 | Respiratory rate 48 | Blood pressure 107/51 | Oxygen saturation 99% on room air

- General: awake, alert, no acute distress

- Eyes: no conjunctivitis

- Mouth: mucous membranes moist

- Neck: no lymphadenopathy

- Lungs: normal work of breathing, lungs clear

- Heart: tachycardic, regular rhythm, no murmur

- Abdomen: soft and non-tender to palpation

- Back: flank is non-tender to palpation

- Extremities: warm, and well-perfused

- Skin: no rashes, capillary refill 2 seconds

- Neuro: age-appropriate behavior

Emergency Department Course

Normal saline bolus and antipyretic were administered. Blood and urine cultures were obtained with pending results.

Laboratory and Imaging

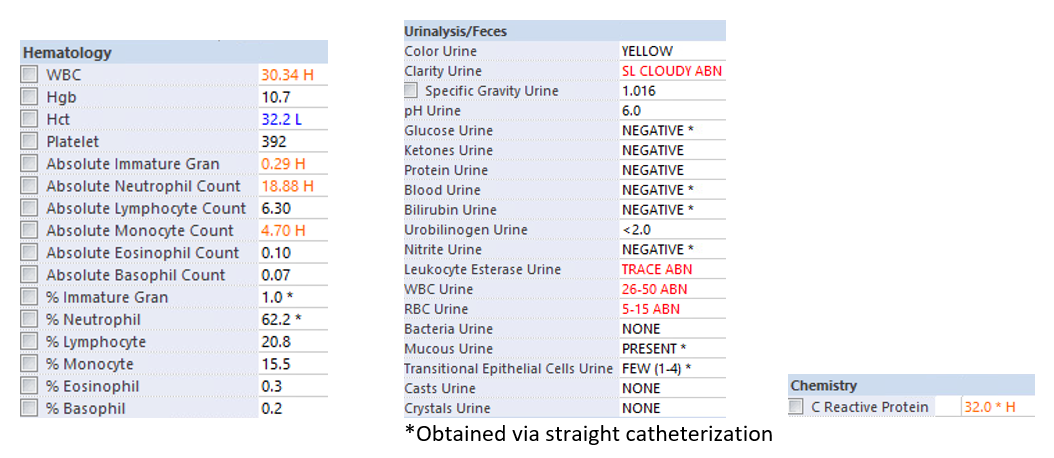

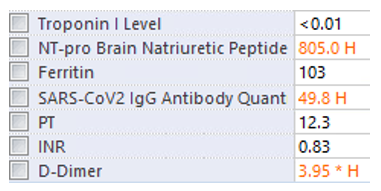

Due to prolonged fevers and significantly elevated inflammatory markers, additional testing for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was obtained.

Questions

1) Which of the following is the next best step in diagnosis?

A. CT scan of abdomen/pelvis

B. Echocardiogram

C. Electrocardiogram

D. Renal ultrasound

2) Which of the following is the next best step in management?

A. Intravenous ceftriaxone

B. Intravenous immunoglobulin

C. Antipyretics + intravenous fluids

D. Intravenous methylprednisolone

Answers

1) D. Renal ultrasound

2) A. Intravenous ceftriaxone

Explanation

This patient has a urinalysis that is positive for leukocyte esterase, with the presence of significant white blood cells. However, no nitrites or bacteria are present, and her leukocytosis and inflammatory markers are perhaps higher than what is anticipated. Urinary tract infection cannot be ruled out, but additional diagnoses should at least be considered.

Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, MIS-C and COVID-19 are considerations for almost every case, due to the non-specific presentations of these inflammatory syndromes. While this patient has an epidemiologic link to COVID-19 (positive IgG antibodies and viral illness two to six weeks earlier), she only has gastrointestinal symptoms and lacks additional clinical features such as rash, conjunctivitis and lymphadenopathy. Under the new American College of Rheumatology guidelines (version 3), this patient should be evaluated for an alternative diagnosis while monitoring for additional features of MIS-C.

In the meantime, given the suspicion for a febrile urinary tract infection, a renal ultrasound can help evaluate for kidney involvement (though not specific for pyelonephritis). A cardiac evaluation would be appropriate if additional features of MIS-C become apparent. A CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis would show evidence of pyelonephritis but would expose the patient to unwarranted radiation without significantly changing the clinical course.

Additionally, ceftriaxone should be started for empiric therapy while cultures are pending. Supportive care with IV fluids and antipyretics alone would be inappropriate, as this patient has a high enough suspicion for an infectious etiology. Empiric administration of intravenous immunoglobulin or steroids would treat MIS-C but are inappropriate until infectious etiologies are evaluated for and ruled out.

Case Resolution

Intravenous ceftriaxone was given in the emergency department and continued while inpatient. Urine culture ultimately grew 4,000 colonies of Escherichia coli. Given that the colony count was technically below the diagnostic threshold for diagnosing a urinary tract infection, an echocardiogram and renal ultrasound were both obtained. Echocardiogram did not show any cardiac dysfunction or coronary artery dilation. The renal ultrasound showed signal abnormality in the left upper pole that was consistent with pyelonephritis (which was her discharge diagnosis). Her fevers improved and she was transitioned to oral amoxicillin at discharge.

Points to Ponder

This case highlights two broad considerations. First, COVID-19 and its complications have certainly affected our diagnostic approach. We must approach every case with and without the lens of SARS-CoV-2 to avoid any forms of cognitive bias. Additionally, we are now ordering labs (D-dimer) for conditions (sepsis) in populations (pediatrics) in which we would not in pre-pandemic practice. Perhaps these labs were always abnormal in these non-MIS-C conditions and we just were not capturing them.

Second, this child did not technically meet the criteria for a urinary tract infection based on the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics Guideline, as her colony count was less than 50,000 (for a catheterized specimen). However, the presence of an appropriate pathogen in culture and the imaging findings supportive of pyelonephritis cannot be ignored and warrant treatment. The “one-size-fits-all” approach regarding colony counts for pediatric urinary tract infections may need to be reconsidered.

References:

- Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology clinical guidance for pediatric patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 and hyperinflammation in COVID‐19. Version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol. Early View. Published online February 3, 2022. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42062

- Guyther J, Cantwell L. Big tests in little people. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2021;39(3):467-478.

- Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021;147(2):e2020012138.

- Molloy M, Jerardi K, Marshall T. What are we missing in our search for MIS-C? Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(4):e66-69.

- Sharma A, Sikka M, Gomber S, Sharma S. Plasma fibrinogen and D-dimer in children with sepsis: a single-center experience. Iran J Pathol. 2018;13(2):272-275.