Disaster Mental Health, A Growing Science and Need Among Pediatric Clinicians

Column Author: Patty Davis, MSW | Program Manager Trauma Informed Care

Column Editors: Chris Kennedy, MD| Division Director, Emergency Medicine, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Angela Guzman, MA, LCSW, LSCSW | Program Manager, Community Behavioral Health, Office for Community Impact

Disasters can happen at any time. Impacts on mental health are important to recognize and abate. For decades now, disaster response efforts have focused on addressing physical wellbeing and community repair.1 In recent years, disaster mental health (DMH) has become a growing area of expertise, focusing on providing psychological support during the phases of disaster preparedness, response and recovery. Catastrophic events can have an impact on behavioral health, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, with higher percentages occurring in youth. These concerns can show up immediately or may develop over years after the initial event.2,3

On Valentine’s Day, 2024, many in Kansas City and surrounding cities and states were exposed to a tragedy occurring at the Chiefs’ Super Bowl parade victory rally. The event, which drew an estimated one million in attendance, was televised to millions more. The rally ended with a violent shooting causing the death of one and physically injuring nearly two dozen others. For a year prior, our city’s law enforcement, emergency medical, fire, and transportation authority worked together to prepare for such a disaster.

Despite the jarring nature of gunshots and terror, our city immediately went into response mode. Victims at the scene were triaged, treated and transported as needed. Police worked to secure the scene. Hospital Command Centers were activated. Health care centers worked to secure a safe entry point for victims and loved ones. Coordination between all disaster response partners occurred. Family reunification plans were activated, and media briefings were conducted. Due to thorough planning, skill and grit, our emergency responders did their jobs exceptionally well that day, taking care of those in need.

However, it soon became clear that with mass violence comes widespread fears and anxieties. These fears are often universal, affecting both young and old, resourced, and non-resourced, those directly exposed and those with vicarious connections to the event.4 Health care team members at Children’s Mercy and in the community began asking how to address concerns coming from patients and families. Staff who were first responders and many others voiced fear and distress related to this tragedy as well. Addressing the psychological impact on children, families, community members and staff quickly became a critical focus for an organization-wide strategic response.5

Ensuring caregivers (health care providers, school personnel, parents, etc.) are well prepared to assess and mitigate mental health concerns following a disaster has been determined to be an essential component of disaster response and recovery planning.1,6 By developing DMH skills, caregivers can provide effective support, instill hope, and maintain structure amid chaos. DMH skills support those in distress2 and boost the caregivers’ confidence in their ability to assist.5

Children’s Mercy conducted hospital and community stakeholder meetings to provide a venue to share resources, maintain open dialogue, increase confidence in addressing trauma, and mitigate gaps in our mental health referral systems. We learned our community caregivers could use trainings to increase provider confidence levels when youth and families present following a disaster.5

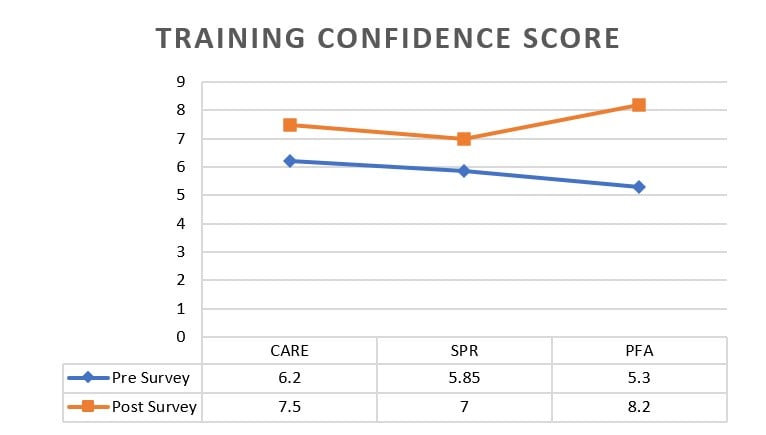

For the next year, and with the support of the Pediatric Pandemic Network, a federal cooperative agreement designed to improve health outcomes of children and the resiliency of children, families and communities impacted by emergencies, disasters and pandemics, Children’s Mercy created access to free trainings for hospital and community members on DMH (e.g., Psychological First Aid, Stress First Aid, Skills for Psychological Recovery, Respond with CARE, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acute Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy). Efforts reached 87 community partners from varied organizations (e.g., Certified Community Behavioral Health Centers, private mental health, health care, school districts, public health, government offices, child welfare, community social services and court systems). Participant caregivers included 282 people from 77 different organizations attending at least one of the trainings within six months. Participant confidence levels increased pre- to post-training as assessed by the question, “What is your current level of confidence in supporting the mental health of children and families impacted by a disaster?” (Figure)

Children and families can show up to their pediatrician’s office at any time following a personal or widespread disaster. The occurrences of catastrophic events, including man-made (e.g., school shootings, terrorism) and natural (e.g., hurricanes, wildfires, flooding) disasters, are becoming more common.1,3 At the same time, schools are more commonly adding active shooter drills to their emergency preparedness plans, which can affect students’ state of mind. Although active shooter drills have shown some improved level of confidence in the case of an attack, students are also showing heightened levels of anxiety and feelings of being unsafe.7,8 Benefits of DMH components, including Psychological First Aid integration and DMH triage, have been shown to minimize the impact of emotional strain and promote recovery.9-11

Parents commonly look to their child’s pediatrician as the expert in areas of concern, such as managing reactions to traumatic stress. By learning how to recognize symptoms, assess needs, and utilize short-term (one-clinic visit) evidence-based interventions, pediatric health care professionals can address these mental health impacts.2,3

Free Learning Opportunities:

The Pediatric Pandemic Network has designed a curriculum to increase clinicians’ knowledge and confidence in addressing mental and behavioral health issues arising from catastrophic events. Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurses, psychologists and social workers.

- Disaster Mental Health ECHO Series: Preparedness and Response to Catastrophic Events

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics has hosted several ECHO series related to disaster management, no series has yet focused on DMH. The Pediatric Pandemic Network is hosting an ECHO series, Disaster Mental Health: Preparedness and Response to Catastrophic Events, for primary care clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs and PAs).

There will be six, 60-minute biweekly ECHO sessions. Each session includes didactics and an anonymous, de-identified case discussion. Continuing education will be provided through the Pediatric Pandemic Network and Children’s National. 1.0 CME will be provided for each session attended (total of 6.0 CMEs).

Please see dates, topics and registration link below.

|

Date |

Topic |

Presenter |

|

June 11, 2025 11-noon CST |

Signs/Symptoms of Trauma Screening and Psychological Triage |

Heather Austin, PhD |

|

June 25, 2025 11-noon CST |

Psychological First Aid |

Patty Davis, LSCSW, IMH-E(III) Sara Anderson, MD |

|

July 9, 2025 11-noon CST |

Anticipatory Behavioral Health Guidance |

Eva Johnson, MD |

|

July 23, 2025 11-noon CST |

Brief Pediatric Psychosocial Interventions |

Kim Burkhart, PhD |

|

August 6, 2025 11-noon CST |

Burnout and Compassion Fatigue |

Kira Mauseth, PhD |

|

August 20, 2025 11-noon CST |

Panel Discussion - Mental Health Crisis/Safety Planning/Referral to ED

|

Nisa Atigapramoj, MD |

Registration here.

- Pediatric Behavioral Health in Disasters online curriculum: Catastrophic events impact children’s mental health. Pediatric Pandemic Network’s new continuing education course helps clinicians recognize symptoms and learn evidence-based interventions. The content presented will follow the four cycles identified in the disaster management cycle: Preparedness, Response, Recovery and Mitigation. This curriculum is designed to be a primer in DMH. Articles provide an overview of key concepts and resources with case examples to illustrate implementation of psychosocial approaches/interventions. Learners will receive guidance in providing just-in-time intervention, identify opportunities for professional growth, and discover actionable steps to improve everyday readiness. Continuing education hours are available. Learn more: Pediatric Behavioral Health in Disasters.

Figure:

Pre-Training Cohort

CARE: N=44 (100%); SPR: N=46 (100%); PFA: N=30(33%)

Post-Training Cohort

CARE: N=11 (25%); SPR: N=11 (24%); PFA: N=11(12%)

Likert Scale

1(not at all confident)-10(extremely confident)

Legend: CARE=Child Adult Relationship Enhancement; SPR=Skills for Psychological Recovery; PFA=Psychological First Aid

References:

- Gold JI, Montano Z, Shields S, et al. Pediatric disaster preparedness in the medical setting: integrating mental health. Am J Disaster Med. 2009;4(3):137-46. PMID: 19739456.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Medical Liability; Task Force on Terrorism. The pediatrician and disaster preparedness. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):560-565. PMID: 16452381. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2751

- Hoffmann JA, Pergjika A, Burkhart K, et al. Supporting children’s mental health needs in disasters. Pediatrics. 2025;155(1):e2024068076. PMID: 39689730. PMCID: PMC11808827. doi:10.1542/peds.2024-068076

- Rancher C, Moreland AD, Galea S, et al. Awareness and use of support services following mass violence incidents. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;180:79-85.

- Davis P, Guzman A, Ray K, Dunleavy M, Slocum K. Meeting the need: a mental health toolkit for disaster response efforts. Poster presented at: Pediatric Academic Society 2025 Meeting; April 26, 2025; Honolulu, HI.

- Pfefferbaum B, Flynn BW, Schonfeld D, et al. The integration of mental and behavioral health into disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2012;6(1):60-66. PMID: 22490938. doi:10.1001/dmp.2012.1

- Miotto MB, Cogan R. Empowered or traumatized? A call for evidence-informed armed-assailant drills in U.S. Schools. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(1):6-8. PMID: 37224233. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2301804.

- Moore-Petinak N, Waselewski M, Patterson BA, Chang T. Active shooter drills in the United States: a national study of youth experiences and perceptions. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(4): 509-513. doi:1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.015

- Schoultz M, McGrogan C, Beattie M, Macaden L, Carolan C, Dickens GL. Uptake and effects of psychological first aid training for healthcare workers’ wellbeing in nursing homes: a UK national survey. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0277062. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0277062

- Abate S, Lausi G, Mari E, Giannini AM, Burrai J. Case study on psychological first aid on Italian COVID-Hospital. J Psychopathology Online First. 2021;Oct 10. doi:36148/2284-0249-438

- Schreiber M, Shields S, Formanski S, Cohen JA, Sims LV. Code triage: integrating the national children’s disaster mental health concept of operations across health care systems. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2014;15(4):323-333. doi:10.1016/j.cpem.2014.09.002