Visual Diagnosis: A Chronic Scaly Rash

Column Author: Sean Reynolds, MBBCH | Associate Program Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Column Editor: Angela L. Myers, MD, MPH | Chief Wellbeing Officer, Center for Wellbeing, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

A 12-year-old boy with a history of vitiligo presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash.

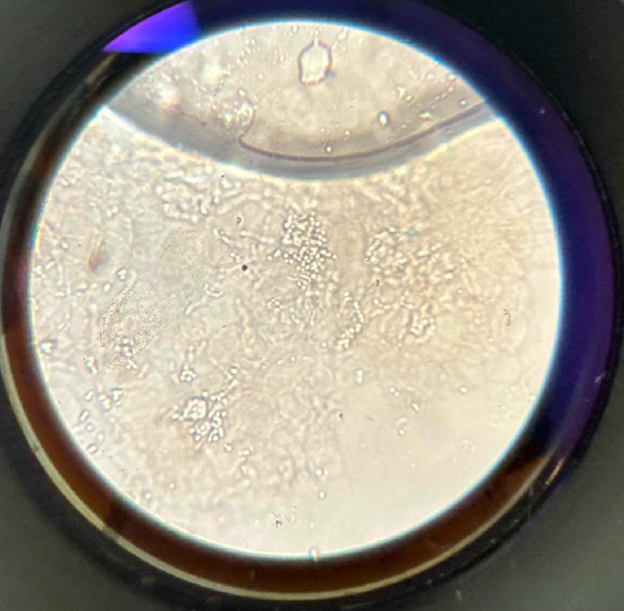

Mother reported that the rash first developed three to four years ago. It started on his neck and eventually spread to his chest, abdomen, back and proximal arms. It has never been itchy or painful or has bled. Mother and patient note that the rash has waxed and waned since onset but never fully resolves. Mother has tried treating the rash with an over-the-counter eczema lotion, without improvement. They have never tried any prescription treatments for the rash. The patient is otherwise feeling well without recent fevers, weight loss, joint pains or fatigue. He is not currently taking any medications. No one else at home or in the family has a similar rash. A KOH preparation was performed on a sample of scale scraped from the rash. An image of the microscopy findings and clinical images of the patient’s rash are shown below.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

- Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP)

- Tinea versicolor

- Vitiligo

- Tinea corporis

- Psoriasis

Answer: B) Tinea versicolor

The patient presents with a waxing and waning eruption of several years’ duration. On examination he has darker brown to pinkish plaques with a fine scale throughout the lesions that is accentuated by rubbing the plaques. The lesions are distributed predominantly on the trunk and proximal upper extremities. The microscopy image demonstrates short hyphae and clusters of fungal spores that confirm a diagnosis of tinea versicolor.

Tinea versicolor, also known as pityriasis versicolor, is a superficial fungal infection caused by Malassezia species, part of the normal skin flora. It commonly presents in children and adolescents as well-demarcated patches or macules with subtle scaling, often on the trunk, neck and upper arms. Lesions may be hypopigmented, hyperpigmented or erythematous, depending on the patient’s baseline skin tone and the stage of the disease. In skin of color, hypopigmented macules are most commonly seen and can be mistaken for post-inflammatory hypopigmentation or early vitiligo. The variation in pigmentation is due to Malassezia-associated interference with normal melanocyte function—either through melanocyte inhibition (causing hypopigmentation) or inflammation and melanin accumulation (causing hyperpigmentation). Diagnosis can often be made clinically by the characteristic appearance, with accentuation of fine scale when the lesion is gently scraped (the “evoked scale” sign). A KOH scraping typically reveals short hyphae and spores, described as the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) can resemble tinea versicolor, especially when it presents as hyperpigmented scaly patches on the central chest or back of adolescents. However, CARP typically begins with hyperpigmented papules that coalesce centrally with a more reticulated pattern peripherally. Recognizing this pattern can help differentiate it from tinea versicolor. The lesions seen in CARP are not hypopigmented.

Vitiligo presents with well-demarcated depigmented (not just hypopigmented) macules that typically lack scale. In contrast, tinea versicolor rarely causes complete depigmentation and has fine scale that can be elicited by scraping. Vitiligo lesions fluoresce bright white under a Wood’s lamp, while tinea versicolor lesions do not. A key distinguishing feature is that vitiligo is often progressive and symmetrical, affecting the periorificial areas and acral surfaces, while tinea versicolor tends to be more patchy and limited to seborrheic areas.

Tinea corporis, caused by dermatophytes rather than Malassezia, presents as annular plaques with raised, active, scaly borders and central clearing. Lesions are usually more inflamed than those seen in tinea versicolor and often itch. KOH prep in tinea corporis reveals septate hyphae, not the spaghetti and meatballs pattern of tinea versicolor.

Pediatric plaque psoriasis can be confused with tinea versicolor when presenting as faintly scaly patches. However, psoriasis plaques are typically thicker with more defined erythema and silvery scale, often located on extensor surfaces, scalp and diaper area. Psoriasis is usually symmetrical and may involve nail changes or have a family history. A positive Auspitz sign (pinpoint bleeding when scale is removed) and chronic course also help distinguish psoriasis from tinea versicolor.

Which of the following is the most appropriate treatment?

- A) Oral griseofulvin

- B) Topical nystatin

- C) Oral terbinafine

- D) Topical ketoconazole shampoo

- E) Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment

Answer: D) Topical ketoconazole shampoo

For children with an initial episode of tinea versicolor with limited skin involvement, topical treatment is often preferable. Topical ketoconazole 2% shampoo, topical selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo or zinc pyrithione 1% shampoo are all treatment options applied daily for one to four weeks for five to 10 minutes in the shower or bath, before rinsing off. Some studies suggest that even shorter treatment courses for topical ketoconazole shampoo, such as daily application for three consecutive days, may be effective. Given the common nature of recurrence, this initial regimen is often followed by a maintenance regimen to prevent recurrence. While these regimens have not been well studied, the use of one of these topical agents weekly or monthly is commonly employed for this purpose.

For recurrent, refractory or more extensive cases, oral treatment may be used. Oral fluconazole or itraconazole is the treatment of choice in patients requiring oral treatment. Fluconazole is typically given once weekly for two weeks and itraconazole daily for five days, although many variations to these regimens are reported in the literature.

For our patient, given the extensive and recurrent nature of his eruption over several years, he was treated with oral fluconazole weekly for two weeks in addition to topical ketoconazole shampoo weekly to prevent recurrence.

Oral griseofulvin, oral terbinafine and topical nystatin are ineffective for treating tinea versicolor. While topical terbinafine has been used to treat limited disease with good effect, oral terbinafine may not be secreted in sweat at high enough concentrations to treat tinea versicolor adequately and should be avoided.

Topical steroids are not effective in the treatment of tinea versicolor.

Of note, many patients, especially patients with skin of color, may have significant residual post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation that can last for weeks to months after appropriate initial treatment of tinea versicolor. This residual effect may cause concern that the eruption has not been adequately treated. In such cases, other clinical signs that can indicate treatment response include resolution of scale and no progression or new lesions after treatment.

References:

- Gupta AK, Batra R, Bluhm R, Faergemann J. Pityriasis versicolor. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21(3):413-429, v-vi. PMID: 12956196. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00039-1

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO. Tinea versicolor (pityriasis versicolor). In: Dellavalle RP, Levy ML, Rosen T, eds. UpToDate. UpToDate; 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tinea-versicolor-pityriasis-versicolor

- Lange DS, Richards HM, Guarnieri J, et al. Ketoconazole 2% shampoo in the treatment of tinea versicolor: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(6):944-950. PMID: 9843006. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70267-1

- Gupta AK, Foley KA. Antifungal treatment for pityriasis versicolor. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;1(1):13-29. PMID: 29376896. PMCID: PMC5770013. doi:10.3390/jof1010013