Pediatric Bioethics: Moral Distress Is Real. What Will We Do With It?

Column Author: Brian Carter, MD | Interim Director, Bioethics Center; Department Chair, Department of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine

Angie Knackstedt, BSN, RN, NPD-BC | Program Manager, Health Literacy & Nursing Bioethics; Co-Director of Certificate Program in Pediatric Bioethics

Column Editor: Amita Amonker, MD, FAAP | Physician Advisor, Care Management and Utilization Review, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

The advances in pediatric health care over the last two decades have been remarkable, from advances in critical care to the development of new clinical services and board certifications in Pediatric Hospital Medicine and Hospice & Palliative Medicine. Children and families are able to look with hope for speedier diagnoses (think genome and exome sequencing) and personalized care that is accessible across care environments in the hospital, at home, or through subspecialty clinics.

Accompanying these advances, which are at times punctuated by specific disease outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics, the health care professionals (HCPs) attending to children and families may be challenged physically, mentally, emotionally, and morally. As we live in a society of people from all corners of the earth, speaking dozens of languages, and carrying numerous cultural heritages, we should not be surprised that there may be values that are occasionally at odds with each other. What one family may consider a goal, an outcome, which is challenging to achieve – even accompanied by significant risk – other families may find untenable. For the HCPs caring for such families, similar dissonance may be present, and emotional, psychological, spiritual, or moral distress may ensue. Some have offered that moral distress is unavoidable when working in critical care environments.1

Five Types of Moral Distress

|

Type of Moral Distress |

Reason for Distress |

Common Emotions |

|

Moral Uncertainty Distress |

Uncertain whether you are doing the right thing |

Torn, conflicted, uncertain, frustrated |

|

Moral Conflict Distress |

Conflicted about the most appropriate ethical action |

Conflicted, frustrated, angry, sad |

|

Moral Constraint Distress |

Constrained from taking ethically appropriate action |

Angry, frustrated, powerless, sense of injustice |

|

Moral Dilemma Distress |

Unable to choose between ethically supportable options |

Guilt, regret, sad, torn, sense of injustice |

|

Moral Tension Distress |

Unable to share your beliefs with others |

Sad, angry, frustrated, powerless |

Based on Morley and Horsburgh / Cleveland Clinic Model – Moral Distress Reflective Debriefs (MDRDs) - Morley, G. 2018: https://research-information.bristol.ac.uk/en/theses/what-is-moral-distress-in-nursing-and-how-should-we-respond-to-it(08e7e5ca-14f6-443d-91a2-b50d4cd00cbc).html

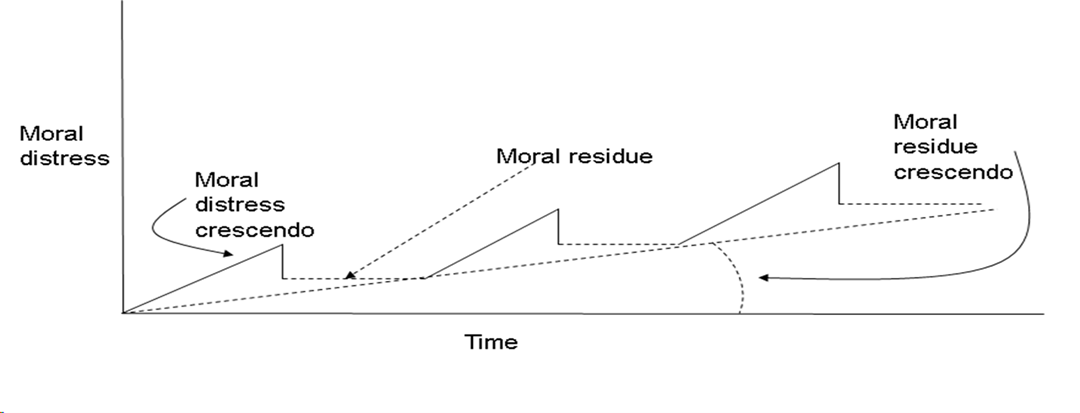

All HCPs need to be able to identify their distress and seek some improved coping skills and means by which they can achieve resilience to continue in their service-oriented professions. Not doing so can lead to unmitigated moral distress that affects HCPs physically, behaviorally, emotionally, and spiritually, as well as possibly causing them to leave a profession that they have trained for and love. Epstein and Hamric described the Crescendo Effect of Moral Distress (illustrated in the diagram below) that transpires over time, leaving moral residue behind each time moral distress occurs and is not mitigated, resulting in a heightened experience and symptoms with each successive occurrence.2

The Crescendo Effect of Unmitigated Moral Distress

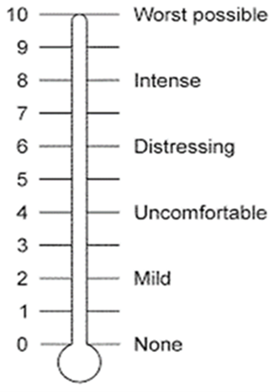

Identifying the source of moral distress and using ethics resources available in one’s institution or community can help HCPs decide to take action to mitigate moral distress. One self-assessment tool that helps describe the amount and severity of the distress is the Moral Distress Thermometer developed by Wocial and Weaver.3 This tool provides a scale to aid in determining one’s needs to track moral distress over time, determine the urgency to act and seek support.

A deeper understanding of the various types of moral distress might help HCPs better cope with it and move to regain their desired resilient selves. Recent work from colleagues in Boston and Milan suggests that there are a number of effective coping mechanisms that clinicians may employ.4

Modified from Ref. 2: General description of strategies & distribution of 105 thoughts/behaviors according to each strategy.

|

Reframing the situation |

Reframe the morally distressing situation: acknowledge limits that are inherent in oneself/others, recognize others’ perspectives, trust others & focus on values that could be upheld despite the constraints |

31 (29%) |

|

Trying to modify the situation |

Try to modify the morally distressing situation by speaking up, raising arguments, taking charge, or seeking help |

24 (23%) |

|

Limiting own involvement |

Detach emotionally from the morally distressing situation to safeguard wellbeing |

13 (12%) |

|

Tolerating the situation |

Passively accept the morally distressing situation |

11 (11%) |

|

Meeting and sharing with colleagues |

Meet & share with colleagues’ support, an exchange of opinions, deliberation, and validation |

10 (9%) |

|

Rejecting and withdrawing from the situation |

Reject & actively withdraw from situations compromising moral values and wellbeing |

7 (7%) |

|

Searching for alternative actions |

Search for alternative actions, given the existing constraints, to uphold moral values |

5 (5%) |

|

Venting |

Venting emotions through communication, recreational or physical activities |

4 (4%) |

Organizations, hospitals and health care systems need to contribute to these matters in positive ways. Support for employee wellbeing is paramount and is more prevalent now than ever before in health care. Creating safe spaces for open discussion of morally challenging situations in the presence of psychological safety allows HCPs to gain understanding of moral distress and ways address it effectively, as well as prevent it in the future. Wellness coaches, psychosocial support through counseling, social work, psychology, spiritual leaders, and ethics are all part of potential solutions.

References:

- Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, Davis PG. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:701-708. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410

- Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics. 2009;20(4):330-342. doi:10.1086/JCE200920406

- Lamiani G, Montecalvo M, Luridiana Battistini C, Borghi L, Meyer EC, Vegni E. Coping with moral distress: a qualitative study exploring psychological strategies used by healthcare professionals. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):589. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02926-3

- Wocial LD, Weaver MT. Development and psychometric testing of a new tool for detecting moral distress: the Moral Distress Thermometer. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):167-174. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06036.x