Outbreaks, Alerts and Hot Topics

April 2021

COVID-19 Incidence in Children Through Young Adulthood and the Promise of Vaccine for Teenagers

Angela Myers, MD, MPH | Director, Division of Infectious Diseases | Professor of Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine | Medical Editor, The Link Newsletter

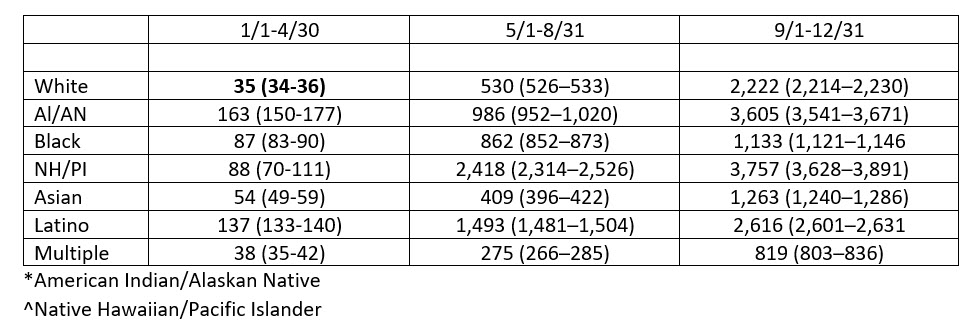

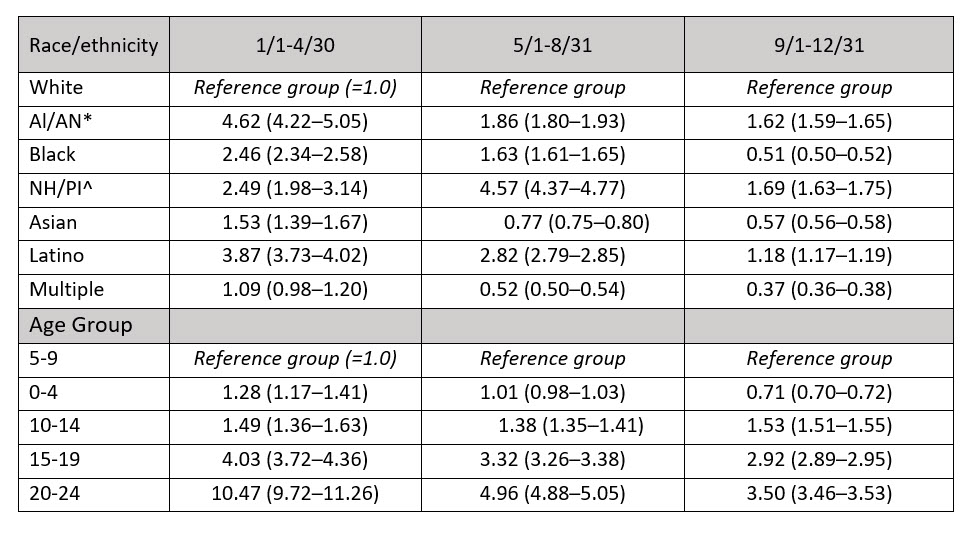

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released new data in early March highlighting the racial, ethnic and age disparities for COVID-19 infections in children and adults <25 years of age across 16 U.S. health department jurisdictions, which included the state of Kansas.1 Over the course of 2020, the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections increased for all races/ethnicities, peaking in the latter third of the year. In the first quarter of the year, incidence was lowest for White persons and highest for American Indian/Alaskan Natives (AI/AN), while in the second and third quarters, incidence was lowest for those who identified as multiple races and highest for Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders (NH/PI). Table 1. Higher rates for AI/AN, NH/PI and Latino persons persisted, while the higher rates of infection in Asian and Black persons declined to be closer to those of White persons in the middle and latter third, respectively. Table 2.

Infection rates in children 0-4 years old were slightly higher in the first third, but were equal in the middle third and lower in the latter third of the year compared to 5- 9-year-olds. However, infection rates in children (10-14), adolescents (15-19), and adults (20-24) remained higher than children ≤9 years throughout the year. Table 2.

What do all these data tell us? First, it reminds us that this pandemic has been dynamic and has affected all racial, ethnic and age groups, albeit affecting some age and racial/ethnicity groups disproportionately throughout. It highlights that the disproportionate decrease in infection rates for non-White races/ethnicities over the course of the year was primarily related to an increase in infection rates in White persons from 35:100,000 during the first third to >2,000:100,000 in the last third, a 63-fold increase.

We are also reminded that early in the pandemic, some groups may have been more affected, at least in part, due to their likely increased and unavoidable exposure risk of being essential workers and/or living in multi-generational households.

Finally, these data highlight the importance of vaccine for people of all races/ethnicities and ages, an increasingly important point for us as pediatricians. Scientists/public health officials (and the news media) have projected that the COVID-19 vaccine may be authorized for adolescents 12 years and up by late summer or early fall. Several phase II/III clinical trials are either underway or are gearing up to compare antibody responses (aka: immunogenicity studies) for the different COVID-19 vaccines to those in adults. This is wonderful news!

However, there are a few caveats to consider as we head toward summer months, the season for pre-school and sports physicals. Currently, the recommendations state that COVID-19 vaccines should not be co-administered with any other vaccine or within 14 days of another vaccine unless the benefits of vaccination are thought to outweigh the as yet unknown risk of vaccinating with an interval shorter than 14 days (e.g., tetanus prophylaxis could qualify).2

This 14-day interval between standard and COVID-19 vaccines appears to create new challenges in the setting of school-based requirements for administering Tdap and meningococcal vaccine prior to middle school entry, and dose #2 of meningococcal in high school. Additionally, the currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines require two doses in adults for full protection with a tight window of three to four weeks for the second dose. Although second-dose intervals can be expanded out to six weeks (or perhaps longer as new data become available), currently there are limited data beyond six weeks between doses; and as we learned with HPV vaccine, it can be hard to get teenagers back for the second dose. In 2019, nearly 70% of those 13-17 years old in Missouri had received ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine, while only a little more than half were up to date.3 That said, many people are motivated to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and get back to their pre-COVID-19 lives, and may be more will be willing to time their school physicals so that interference with the ability to receive the COVID-19 vaccine is minimized.

Table 1. Incidence of COVID-19 infection per 100,000 by race/ethnicity for the calendar year 2020. Note the very low rate for Whites in the January to April timeframe and the large increase in the September to December timeframe.

Table 2. Rate ratios of COVID-19 infection by race/ethnicity and age group for the calendar year 2020.

References:

- Van Dyke ME, Mendoza MC, Li W, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 incidence by age, sex, and period among persons aged <25 years-16 U.S. jurisdictions, Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 10 March 2021. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7011e1.

- Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html

- Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/teenvaxview/data-reports/hpv/dashboard/2019.html