Evidence-Based Strategies for Common Clinical Questions

April 2021

Trust Your Gut; It’s Not All In Your Head

An Approach to Functional Disorders

Author: Daniel Mulhall, MD | Chief Resident of Pediatrics

Column Editor: Kathleen Berg, MD | Pediatric Hospitalist, Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine | Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

Your 15-year-old patient was in honors classes and had a robust social life, but is now quitting soccer, frequently missing school, and struggling to pass due to frequent abdominal pain and headaches. Comprehensive medical evaluation has been unremarkable. Such patient scenarios are common and quite challenging. Traditionally, medical training teaches us to rule in and rule out. We learn to categorize pathology as structural or psychiatric, leaving us less prepared to evaluate and treat the increasingly recognized group of functional disorders.

Functional disorders are particularly challenging in pediatrics, as our patients are often less able to describe their symptoms and their caregivers may expect a different diagnosis.1 This yields a culture which places significant emphasis on physical symptoms. This leads to increased diagnostic testing and subspecialty referral, an approach which can result in dissatisfaction and mistrust without a clear path for recovery.2

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, functional disorders are constellations of “bothersome physical symptoms that compromise regular function but for which there is no identifiable organic or psychiatric pathology.”3 Symptoms negatively impact a patient’s activities. Common types include functional neurologic disorder (previously known as conversion disorder), functional gastrointestinal disorder, chronic pain and chronic fatigue. An estimated 20% of pediatric patients in neurologic and psychiatric practices are affected by functional disorders.4 Approximately 25% of children aged 4-18 years meet criteria for a functional gastrointestinal disorder (including functional constipation).5

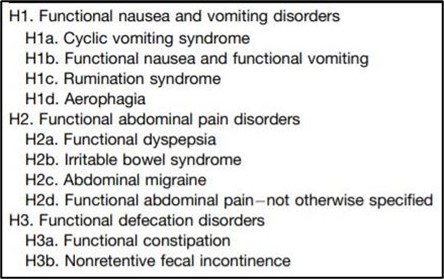

While functional disorders may be difficult to conceptualize, there are evidence-based diagnostic strategies to serve as our guides. Rome IV includes diagnostic criteria for each of the functional gastrointestinal disorders listed in Table 1.6 Each includes specific conditions for frequency and duration of symptoms, as well as presence or absence of certain associated symptoms. The updated criteria replace the need for “no evidence for organic disease” with “after appropriate medical evaluation the symptoms cannot be attributed to another medical condition,” allowing clinicians to conduct more selective or even no diagnostic tests.7

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, provides updated diagnostic criteria for functional neurologic disorders. It substitutes the term “psychogenic” with “functional” and no longer requires known psychologic stress as a prerequisite for diagnosis.7-9 A shift away from functional disorders as a diagnosis of exclusion, but rather as an early consideration in the differential, lends it legitimacy in the eyes of patients and promotes purposeful, high-value care. Clinicians should continue to screen for potentially modifiable triggers such as stress or abuse and recognize that functional disorders may coexist with other medical conditions.10

Once a functional disorder is diagnosed, providers must effectively communicate the diagnosis to the patient and caregivers. This includes addressing misconceptions that an illness belongs completely to the physical or mental realm, or that validating the concerns somehow promotes the symptoms.1 Clinicians should provide encouragement that the condition is reversible. Conveying empathy and commitment to the patient is critical for acceptance, increasing the success of a therapeutic plan.

The model of a “Roadmap to Recovery” focuses on three treatment modalities: continuity with an appropriate care provider, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and regular physical activity.3 CBT helps patients develop coping mechanisms and mitigate stress as they work toward resumption of regular academic, social and physical activities. Implementation of a biopsychosocial model of care, including CBT, was associated with recovery in 60% of children with functional gastrointestinal disorders within 1.5 years.8 A meta-analysis of 21 randomized controlled trials found that psychological treatment was associated with decreased symptom load, disability and school absence in children with functional neurologic disorders.11 Collaboration is particularly important for adolescents to avoid cognitive dissonance with their diagnosis and treatment. A multidisciplinary team can assist by reaffirming the validity of the diagnosis and necessity of both therapy and reintroduction to activity. Subspecialty and primary care providers should work in conjunction to promote frequent follow-ups with consistent positive messaging.

With updated tools to diagnose and treat functional disorders, we move past the outdated assumptions that “nothing is wrong.” We can view these disorders as neither structural or psychiatric disorders, but functional, in which the mind and body are not collaborating effectively. While scientific advancements may later reveal new explanations for some, that should not deter clinicians from diagnosing and validating functional disorders.

Table 1. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents with Rome IV diagnostic criteria.6

References:

- McKnight R, Price J, Gelder MG. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. Psychiatry. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2019. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198754008.003.0033.

- Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: An epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res. 2001 Jul;51(1):361–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00223-9.

- Sunde KE, Hilliker DR, Fischer PR. Understanding and managing adolescents with conversion and functional disorders. Pediatr Rev. 2020 Dec;41(12):630-41. doi:10.1542/pir.2019-0042.

- Feinstein A. Conversion Disorder. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018 Jun;24(3):861–72. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000601.

- Robin SG, Keller C, van Tilburg MAL, et al. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the Rome IV criteria. J Pediatr. 2018 Apr;195:134-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.012.

- Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, van Tilburg M, et al. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb;15:S0016-5085(16)00181-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013.

- Shailender M, Parikh S, Madani R, Krasaelap A. Long-term study of children with ROME III functional gastrointestinal disorders managed symptomatically in a biopsychosocial model. Gastroenterology Res. 2017 Apr;10(2):84–91. doi:10.14740/gr798w.

- Espay A, Aybek S, Morgante F, et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Sep 1;75(9):1132-41. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1264.

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Stone J, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;5(4):307–20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30051-8.

- Bonvanie IJ, Kallesøe KH, Rask CU, et al. Psychological interventions for children with functional somatic symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2017 Aug;187:272-81.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.017.