Living with HLHS: Jaxon’s Story

Meet Jaxon

Jaxon Kuhn, 16, can tell you exactly how many days it’s been since he got his driver’s license. He likes watching movies and playing video games with his friends. The high school sophomore has hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), but the diagnosis doesn’t rule his life, thanks to excellent care from Children’s Mercy Kansas City and the support of his family.

When Jaxon’s mom, Traci Kuhn, was nearly six months pregnant, she woke up one morning knowing something was wrong. She had no symptoms but convinced her doctor to give her another sonogram. “Within minutes, they came back in and said, ‘We need to send you to Children’s Mercy,’” remembered Traci. She and her husband, Greg Kuhn, came in for more screening and discovered their baby had HLHS, a congenital disorder that affects 1 of every 3,800+ newborns in the U.S. every year.

Babies with HLHS have hearts with underdeveloped left sides. Usually, the left side of the heart takes in oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it out to the rest of the body. When the left ventricle and other structures either aren’t formed or are very small, the body can’t get enough oxygenated blood. “When I started my training, HLHS was lethal,” said Stephen Kaine, MD, FAAP, FACC, Medical Director, Cardiovascular Laboratories, Ward Family Heart Center. “Now kids with HLHS can live very normal lives.”

Traci and Greg learned their baby would need three surgeries over several years to help the heart function with only one developed ventricle.

“The three-stage surgical palliation only became routine in the mid-’90s,” said Jaxon’s surgeon, James O’Brien, MD, FACS, Co-Director of the Ward Family Heart Center and Chief of Cardiothoracic Surgery. “And the care surrounding children before their first and second surgeries has really improved; that used to be a significant risky time.”

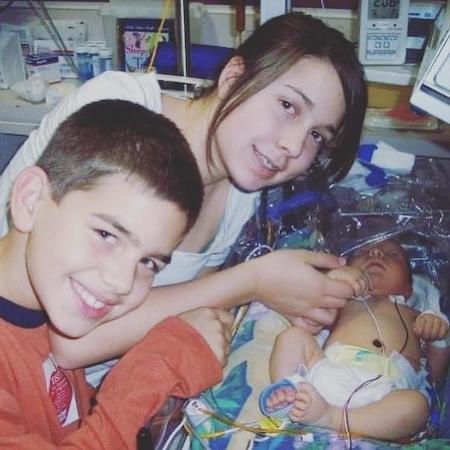

Jaxon was born Nov. 9, 2007. Traci had a scheduled C-section at another hospital, and Greg went with Jaxon by ambulance to the Children’s Mercy Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). The NICU team stabilized Jaxon and helped the family prepare for Jaxon’s first surgery.

Traci checked herself out of her hospital early because she wanted to be near Jaxon. At 10 days old, he had a Norwood procedure surgery, which allows the right ventricle to pump blood to both the lungs and body. When Jaxon was 31 days old, they got to go home.

They had six months to soak up family time with Jaxon’s older siblings, Isayah and Maya (Maya is now a marketing coordinator at Children’s Mercy), before his second surgery — a bi-directional Glenn Shunt procedure that connected the “blue” blood coming back from the upper body directly to the lungs to get reoxygenated.

After his second surgery, Jaxon had time to grow. He was a busy toddler, three and a half, for his third surgery and more aware of what was happening.

“Even though he’s been to all the doctor’s appointments and loved his cardiologists, taking him back for that one was the hardest part,” said Greg.

The surgery, a Fontan procedure, directed the lower body’s oxygen-poor blood to the lungs and completed the standard HLHS surgery series.

Life with HLHS

The memories of those surgeries have faded for teenager Jaxon. “I remember playing at Children’s Mercy, but that’s about all,” said Jaxon. “I remember coming home and seeing the ‘Welcome Home’ that Maya and Isayah wrote on the sidewalk.”

Thanks to his care team, family and a little luck, Jaxon has grown up without many HLHS complications. As a teenager, he's learning to take ownership of his health care in preparation for when he ages out of the Children’s Mercy system. He meets every six months with Dr. Kaine, who was on his original care team and became his outpatient cardiologist in 2016.

Care for adolescent and adult patients with HLHS is still evolving. “Adults with congenital heart disease need specialized care,” said Dr. Kaine, “and we are building that network here in Kansas City.” Children’s Mercy and Saint Luke’s Hospital are working to formalize that mission by applying for a certification from the Adult Congenital Heart Association.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen as these patients get into their 30s, 40s and 50s,” said Dr. O’Brien, adding that current HLHS research is focused on improving quality of life. “Jaxon is part of a story that is still being written.”

Dr. Kaine explains that Jaxon’s unique physiology can put extra stress on the liver, so he has regular check-ins with the hepatology team. HLHS patients also need to watch out for endocarditis, an infection inside the heart, and irregular heart rhythms. So far, Jaxon has been healthy. Because he only has one ventricle, his exercise capacity and stamina can be affected. Dr. Kaine encourages recreational fitness for HLHS patients and guides the competitively minded toward skills-focused sports that aren’t dependent on high-intensity running (such as baseball, softball and volleyball).

Sharing what they’ve learned

Jaxon advises younger HLHS patients to focus on what you can do, not your limitations.

“You’re probably a little different than the other kids,” said Jaxon. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t do what they do, you know?” Telling friends at his new school about his diagnosis was a nonevent. “It really doesn’t change anything.”

Traci and Greg also emphasized parents should take care of themselves, engage with a support group, and involve siblings in conversations and plans.

“They don’t write a manual for how to feel as a parent in these situations,” said Greg. “Children’s Mercy staff spend the time and effort it takes for you to understand the process and the plan. Jaxon wouldn’t be here without each and every one of them.”

“Trust the doctors and nurses,” echoed Traci. “But also don’t be afraid to ask questions, follow your intuition and advocate for what you want to see happen.”