Outbreaks, Alerts & Hot Topics: American Trypanosomiasis in the US

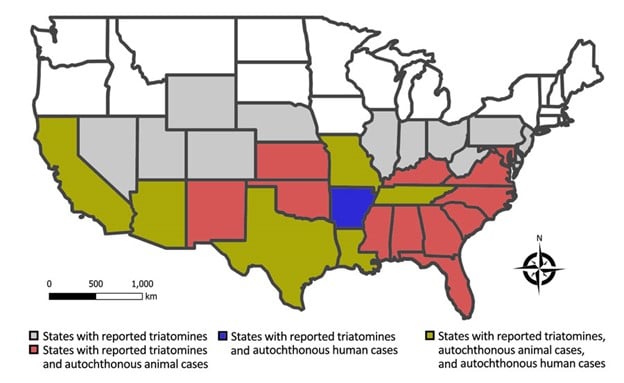

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, has long been considered a disease from “south of the border,” relevant in the United States mostly because of large numbers of immigrants from mainland Latin America. However, a recent article in Emerging Infectious Diseases1 led to a brief surge of publicity by suggesting that instead of considering Chagas disease nonendemic in the United States, it should be acknowledged that vector-borne transmission occurs domestically, though at a low level (hypoendemic). Cases of autochthonous (domestically acquired) vector-borne Chagas disease in the United States (Figure 1) have been uncommonly (28 cases documented from 1955 to 2015, mostly in Texas), but steadily reported and include at least one case with transmission apparently occurring in Missouri.2 Human cases (including the case in Missouri) are now being detected as a result of blood donor screening, which was first implemented in 2007. Cases in dogs are more common and widespread, having been documented in 23 states, including 451 canine cases in Texas from 2013 to 2015.1

While there is little to no evidence that the risk to humans of acquiring the Chagas disease parasite (Trypanosoma cruzi) in the United States is increasing, more autochthonous cases are being detected. From 2000 to 2018, there were 29 confirmed and 47 suspected such cases. These were associated with “rural residence, history of hunting or camping, and agricultural or outdoor work.”1 Texas alone, where more efforts are being made to find cases, saw 50 probable and confirmed cases from 2013 to 2023. According to the authors of the Emerging Infectious Diseases article, the hope is that considering the United States to be hypoendemic rather than nonendemic will increase awareness and “improve surveillance, research, and public health responses.” The authors also recommend better training of providers in recognition of Chagas disease.1

In Latin America, Chagas disease is a better-known infection. In 2023, it was responsible for 10.5 million prevalent infections and 8420 deaths, most of these in southern and Andean Latin America.3 There are estimated to be 300,000 to 1 million active cases in the United States, mostly in immigrant populations from these regions.4 The parasite is transmitted by an insect vector, by oral ingestion, and also vertically in perhaps 1%-5% of pregnancies where the mother is infected. Transmission through blood (especially platelet) transfusion, organ transplantation, and possibly breastfeeding also occurs. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Mothers with Chagas disease can usually breastfeed safely. But, if a mother has cracked nipples or blood in her breast milk, it is best to pump and throw away the milk until her nipples heal and the bleeding stops.”5 One study did identify T. cruzi DNA in breastmilk.6 A thorough discussion of the issues surrounding Chagas disease and breastfeeding is found in a 2013 paper in Emerging Infectious Diseases.7

The insect vectors of American trypanosomiasis are members of subfamily Triatominae (family Reduviidae), known commonly as kissing bugs (Figure 2), conenose bugs or vampire bugs. Most of these insects feed on blood, usually at night. Only a few species have adapted to living around humans; these tend to be the more important vectors of human disease. Transmission of the parasite is maintained in the wild with mammalian reservoir hosts. Domestic animals such as cats, dogs and guinea pigs can also serve as reservoirs. Triatomine bugs are associated with low-quality housing that provides crevices for them to hide. Thatched roofs are attractive to some species. The trypanosome parasite is not transmitted through the insect bite, but instead through the insect’s feces, which may be rubbed into the bite wound after the insect departs (the feces causes pruritus).

Oral transmission can occur when food or drink is contaminated by triatomine bug feces. This is a significant source of transmission in some locales and is associated with consumption of a variety of fruit and plant material, prominently sugar cane, acai, and some fresh fruit juices. The parasite can survive several days in some juices at room temperature and as long as two weeks in some cases with refrigeration. Most of the data about oral transmission has come from large outbreaks, some with rates of mortality as high as 44%.5

Chagas disease often is asymptomatic initially or has mild, nonspecific symptoms that do not come to clinical attention. Acute symptomatic Chagas disease typically begins one to two weeks after infection with swelling at the site of inoculation called a chagoma. This is typically on the face or extremities. When the conjunctiva is infected, swelling of the eyelids (Romaña’s sign) can occur. Severe disease is rare, but can present with pericardial effusion, acute myocarditis or meningoencephalitis. Diagnosis of acute Chagas disease can be made by microscopy of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat or by PCR.

Chronic Chagas disease is typically diagnosed by serologic detection of IgG antibodies to T. cruzi. A single positive test must be confirmed with a second test for antibodies to a different antigen. Chronic manifestations arise over years with destruction of ganglion cells causing denervation, typically causing either heart disease or gastrointestinal disease. The heart disease can result in heart failure, arrhythmias, systemic and pulmonary thromboembolisms, and chest pain. Gastrointestinal disease causes poor peristalsis, especially of the esophagus or colon, and can lead to massive dilation of the viscus.

Antitrypansomal drugs (benznidazole or nifurtimox) are recommended for patients with acute, reactivated (as from new immunosuppression), or congenital infection, as well as children with chronic infections and adults up to age 50 who do not have advanced cardiomyopathy. Both medications can be poorly tolerated. There are promising new drugs under development that may be better tolerated.

Figure 1: Triatomines and cases of Chagas disease in the United States (Source: reference 1)

Figure 2: Three species of kissing bugs potentially responsible for autochthonous transmission in the United States (from left to right): Triatoma protracta (western U.S.), T. gerstaeckeri (Texas), and T. sanguisuga (eastern U.S.). Only adults have wings, but all insect life stages require blood meals. The largest insect pictured here is approximately 1 inch (2.3 cm) from tip of proboscis to tip of abdomen. Photo Credit: By Curtis-Robles et al. - doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004235, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45709021

References:

1. Beatty NL, Hamer GL, Moreno-Peniche B, Mayes B, Hamer SA. Chagas disease, an endemic disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025;31(9):1691-1697. doi:10.3201/eid3109.241700

2. Turabelidze G, Vasudevan A, Rojas-Moreno C, et al. Autochthonous Chagas disease — Missouri, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:193-195.

3. GBD 2023 Chagas Disease and RAISE Study Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Chagas disease, 1990-2023: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet Infect Dis. Published online November 4, 2025. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00562-6

4. Kissing bugs and Chagas disease in the United States: a community science program. Texas A&M Agriculture and Life Sciences; Texas A&M Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. 2025. https://kissingbug.tamu.edu/

5. About Chagas disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chagas/about/index.html

6. Crisóstomo-Vázquez MDP, Rodríguez-Martínez G, Jiménez-Rojas V, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi DNA identification in breast milk from Mexican Women with Chagas disease. Microorganisms. 2024;12(12):2660. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12122660

7. Norman FF, López-Vélez R. Chagas disease and breast-feeding. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(10):1561-1566. doi:10.3201/eid1910.130203

8. López-García A, Gilabert JA. Oral transmission of Chagas disease from a One Health approach: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2023;28(9):689-698. doi:10.1111/tmi.13915

Medical Director, Immune Compromised Service & Special Immunology Clinic; Medical Director, International Travel Clinic; Medical Director, Travel Medicine Program; Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Chief Wellbeing Officer; Professor of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine; Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine