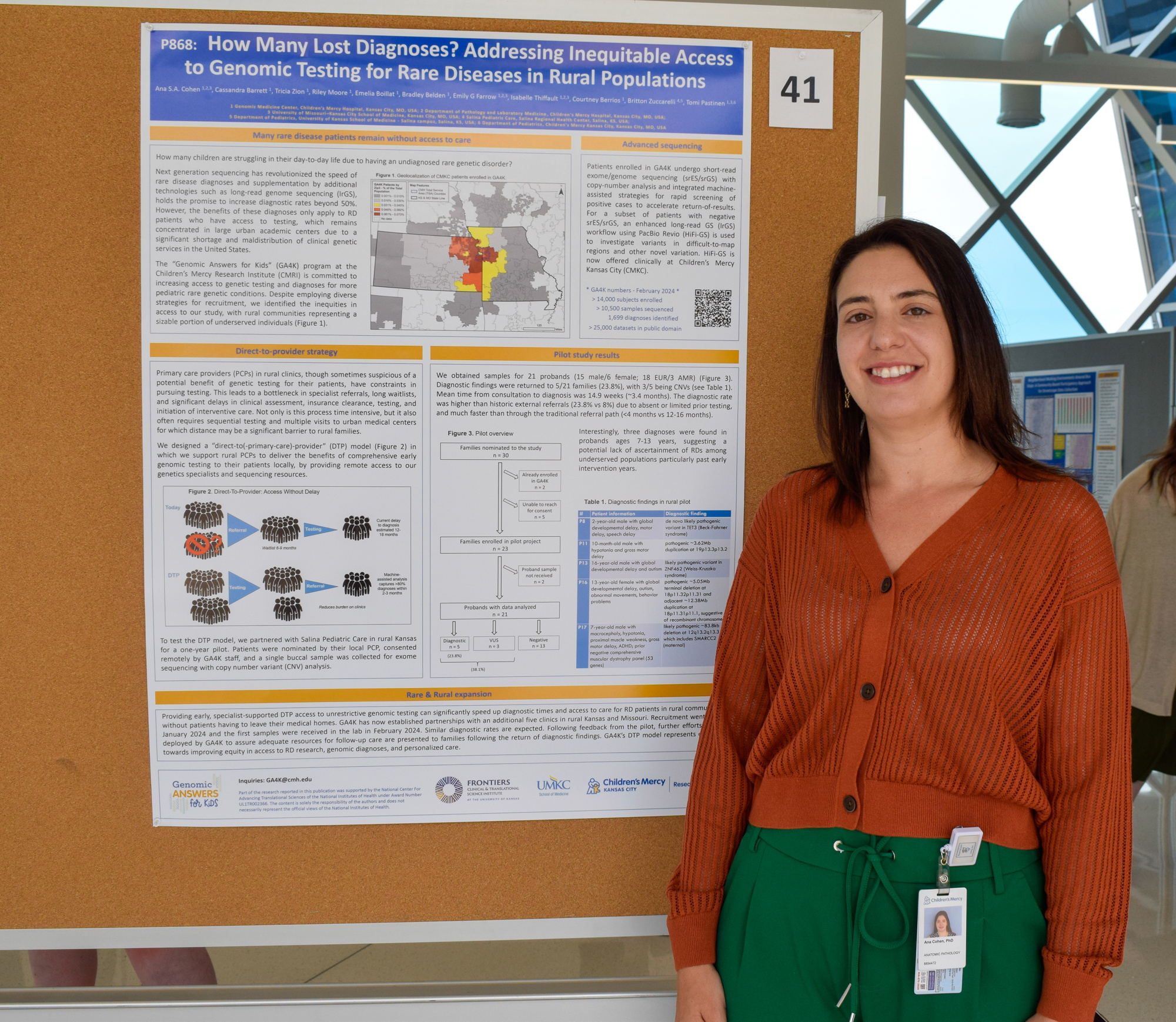

Ana Cohen, PhD, FACMG

Assistant Director, Molecular Genetics; Associate Professor of Pathology, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine

Full Biography

It wasn’t a fascination with how the body works. Instead, it was her passion for learning about people and their origin stories that brought Ana Cohen, PhD, FACMG, to the field of genetics.

“I remember in high school getting assigned homework about collecting my family history and drawing my family tree,” she said. “I just loved sitting with my family and hearing stories about where they came from.”

She dove headfirst into genetics, eventually pursuing a clinical fellowship in laboratory genetic diagnostics. Originally from Portugal, Dr. Cohen moved to the U.S. in 2017 and joined Children’s Mercy in 2020, now serving as Assistant Director of Molecular Genetics and Associate Professor of Pathology at University of Missouri – Kansas City School of Medicine.

Even in the middle of the pandemic, Dr. Cohen said, the timing was nevertheless perfect.

“The diagnostics lab at Children's Mercy was about to transition to the new research tower and was looking to expand in research and translational science,” she said. “I wanted to pursue both clinical and research work. It felt like the right fit right away.”

Pilot program kick-starts emphasis on rural genomic research

A year later, Dr. Cohen became an investigator on studies to evaluate the demographics of participants enrolled in Genomic Answers for Kids, a large-scale genomic rare disease program based at Children’s Mercy. The program collects health information from families affected by rare genetic disorders, testing both the child and their family members to get answers. However, the team’s research found some glaring discrepancies in enrollment between families who lived near a major city as compared to those who were in rural communities.

“It was very clear the enrollment was uneven in terms of where these families were living, and that led us to brainstorm some ideas: How could we serve the families with less opportunity to participate in genomic research? We were shedding a light on exactly what we expected — that there are families without access to what we would consider first-line testing for genetic disorders, simply because of where they live.”

Cohen saw an opportunity to focus on rural primary care providers, to not only increase recruitment but also accelerate the diagnostic rates. She wrote an application for funding through the Lauren S. Aaronson Frontiers Clinical and Translational Research Pilot Program.

“When that came through, we were like, ‘OK, this is the perfect opportunity to test this out to see if this works,’” she said. “And the pilot went better than we expected!”

The pilot also exposed what Cohen calls the “not-so-great parts” that the team would need to overcome — everything from challenges in recruiting from remote areas to matching patients with a specialist provider for follow-up when the nearest children’s hospital is hours away. Even the basic logistics of shipping samples from remote areas caused a few roadblocks.

“It made us realize we take a lot for granted,” she said. “We learned to turn it around. Providers are too busy, so they're not going to adapt to a new system. And families are already so overwhelmed with everything. We want it to make it as easy as possible for everybody.”

Program pushes for increased access, regardless of geography

After starting with a pediatric practice in Salina, Kansas, the research now continues under the Genomic Answers for Kids program and is currently partnering with four more clinics in rural Kansas while applying for additional funding to expand. Cohen and the team are already in talks with providers in Columbia, Missouri, and even recently submitted a grant application with partners in California.

“We're exploring how we can make this more accessible in all sorts of avenues,” she said.

Despite the challenges, Cohen said she’s energized by the research and the important ramifications it can have for so many families.

“You shouldn't have less access to care or research just because you don't live close to it,” she said. “We're always thankful for any family that joins our research study because they’re helping not only themselves but every other family involved. Our data is used by other academic institutions doing similar work with rare diseases, and together we can make more diagnoses in the world.”

You can learn more about team members who are advancing the Children's Mercy pediatric footprint in the FY25 Research Annual Report.