Wide World of Vaccines

February 2022

FDA Delay and Lack of Seroconversion with Mild COVID-19 Disease?

Column Editor: Christopher Harrison, MD | Professor of Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine | Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Kansas School of Medicine

Delayed COVID-19 vaccine EUA for 6-month to 5-year-olds. The emergency use authorization (EUA) will not be until at least May or June. If the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wanted only more analysis of existing data, only a few weeks would be required. But the FDA seems to want to see results of three-dose protocols that just started in February. The three-dose data could come from two groups:

- Children from the original two-dose study getting a third dose. It would likely take until mid-March to get willing study subjects back for third doses and then another one to two months to follow them for safety data and antibody studies.

- New subjects getting three doses at two-month intervals. It is hoped that enrollment would be completed in a month, three doses administered over four months, with one to two months to complete safety data and antibody studies.

If no new adverse effect signals occur, we can expect the critical immunogenicity data needed for an EUA to be available from Group 1 by mid-April. Data verification and analysis could take another two to four weeks. If these data are what the FDA needs, then the FDA review would likely take two to four weeks, with EUA approval by the end of May or sometime in June. Investigators would continue to follow Group 1 for longer-term safety immunogenicity and efficacy.

If, however, the FDA requires immunogenicity data on the newly enrolled group (Group 2), an EUA might not occur until July. So, for the time being, the best way to protect 6-month to 5-year-olds is to be socially safe, to use appropriate masking, and to make sure those around the unimmunized are vaccinated.

What! Seronegative after mild infection? The U.S. is not going to get vaccine-induced herd immunity for many reasons (politics, religious beliefs, conspiracy theories, imperfect messaging about the science of the virus and the vaccine, pandemic fatigue, and sometimes just downright stubbornness). And we are still losing 2,000-3,000 souls to the pandemic daily as of the second week of February. So, how do we best use vaccines whether a person has been previously infected or not?

To understand what blend of vaccine-induced and infection-induced immunity could help protect as many people as possible in the current (even if it is waning) Omicron surge, we need to understand how much protection occurs from infection. That is, does “natural immunity” from SARS-CoV-2 infection protect against subsequent reinfection?

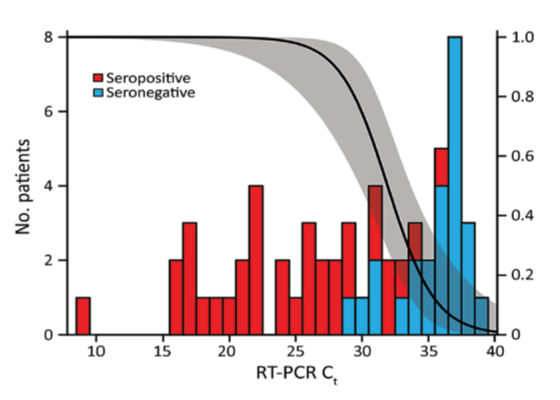

Though we can’t cover all the details in this column, we can look at recent impactful data revealing that not all SARS-CoV-2-infected patients develop sufficient immunity to be protected against reinfection or disease and may actually not seroconvert, Figure 1.1,2 In this study, seroconversion was evaluated by age and by amount of virus in respiratory samples during infection.

In Figure 1, note that low viral load, as indicated by high Ct values, is associated with more likelihood of not seroconverting (blue color). A high Ct value means that the PCR test had to repeat a higher number of cycles to find the small amount of virus present. These seronegatives appear to come from the patient subset with low viral loads during infection (high Ct values).

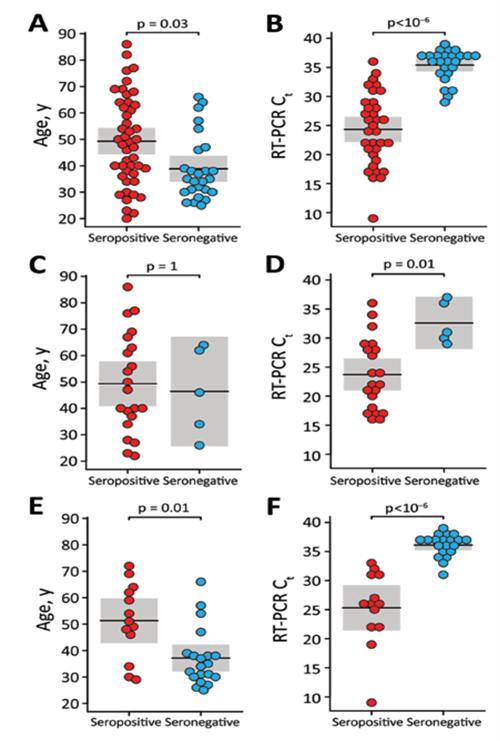

But if our COVID-19 tests are not quantitative, i.e., reported as positive vs. negative not as Ct values, are there clinical clues to recognizing poor responders? We expect suboptimal responses from immune-compromised persons or those over 60 years old, but these new data suggest that young age (25-50 years old) is one clue, Figure 2.1 A sizable proportion of younger immunocompetent persons failed to seroconvert. Further, milder disease also seems to be a clue. In other words, if the younger person controls the infection too well and the infection is mild, then the immune system may not “see” enough virus antigen, making the immune response from mild infection alone inadequate for protection from reinfection. This response is like getting too low a dose of vaccine or getting only one of a three-dose regimen. The milder low viral load infection acts as a partial priming event but does not produce protective immunity, i.e., partial immune memory occurs but not enough antibody is produced.

This nonprotective response to infection during mild disease in younger adults may explain many SARS-CoV-2 reinfections, which now appear to be partly because of poor response to initial infection and partly due to mutations in new variants (looking at you, Omicron) rendering any existing antibody less effective.

What does this all mean? These data have implications for the debate over the need for vaccinating persons who have documented prior infection. It seems the best way to ensure a protective response is to vaccinate even if a person has had a known COVID-19 infection. The infection is a reasonable priming event, but how many vaccine doses might be needed for best protection against reinfection – one or two doses?

My opinion is that the known infection could be substituted for one of the two priming doses of our current mRNA vaccines. Currently per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the first two doses qualify one as fully vaccinated, while adding the third dose qualifies one as “up to date.” The CDC also recommends that all qualified persons be up to date, i.e., get a third dose. If immune-compromised, a fourth dose is also recommended.3,4 So, for those with known prior infection, each event (infection or vaccine dose) gives the immune system a chance to see viral antigen. For example, one dose of vaccine and one documented infection would be similar to the two priming doses of vaccine. Then the question arises about third or booster doses as currently recommended by the CDC. If I had “hybrid immunity” (one vaccine dose combined with prior infection), I would get a booster vaccine dose three to six months after the last of the two prior viral antigen experiences, whether it was vaccine or documented infection. These non-seroconversion data also make it difficult to support the concept that health care workers do not need vaccination if they were previously infected, as argued in a recent op-ed.5

The other implication of non-seroconversion after mild infection is the question of how safe we should feel about contact with a person who claims immunity after mild COVID-19 disease. This question brings to mind a certain tennis player’s claim. I for one would not feel safe in the presence of a person whose only immunity stems from a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Wearing masks and distancing if indoors would still be my approach. Also remember that “natural” immunity from Alpha or Delta is less protective against Omicron than prior Omicron infection.

Last, one has to wonder if the lack of seroconversion in healthy adults may have parallels in mild pediatric infections. Hopefully, data on children will be forthcoming that offers information and recommendations about initial vaccine and booster shots for previously infected children.

Figure 1. Predictive value of low viral load (as represented by high Ct value) in patients tested at three different testing sites.1 The higher the Ct value (lower viral load), the more likely seroconversion did not occur after infection.

Source: Reference 1. Emerging Infectious Diseases is open access, peer reviewed journal published monthly by the CDC.

Figure 2. Age in SARS-CoV-2 convalescent patients tested at three study sites (panels A, C and E), plotted against seropositivity or not.1 Seronegative patients were overall younger although overlap exists, particularly in panel C. Ct value of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR assays (viral load is lower if Ct value is higher) from three study sites (panels B, D and F), plotted against seropositivity or not. Seronegative patients had significantly higher Ct values.

Source: Reference 1. Emerging Infectious Diseases is open access, peer reviewed journal published monthly by the CDC.

References:

- Liu W, Russell RM, Bibollet-Ruche F, et al. Predictors of nonseroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(9):2454-2458. doi:10.3201/eid2709.211042

- Davido B, Jaffal K, Annane D, Lawrence C, Gault E, De P. Predictors of nonseroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(2):492-493. doi:10.3201/eid2802.211971

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html

- McGonagle DG. Health-care workers recovered from natural SARS-CoV-2 infection should be exempt from mandatory vaccination edicts. Lancet Rheumatol. Published online February 2022:S2665991322000388. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00038-8