What's the Diagnosis?

June 2022

Visual Diagnosis

Column Editor: Joe Julian, MD, MPHTM, FAAP | Hospitalist, Internal Medicine - Pediatrics | Clinical Associate Professor, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, UMKC School of Medicine

A 16-year-old female is directly admitted from a referring hospital for further evaluation and management of an abnormal chest radiograph. The patient has had fevers for the past two weeks with associated productive cough (yellow sputum without blood), chills, night sweats and headache. She has an unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds during this time. No associated sore throat, rhinorrhea or rashes.

She has not had any travel outside of her metro-based location in Kansas for the past two years. She has not spent any time in a juvenile detention center, group home, or with anyone from a tuberculosis-endemic country. Several extended family members with a history of incarceration have spent time around the patient but have no history of active coughing or febrile illness. She does not use intravenous drugs or have unprotected sexual intercourse.

Approximately six weeks prior, the patient took a significant amount of sleeping pills and a friend “pumped her stomach” with their hands. She is unsure if she vomited and did not seek medical attention after this episode. She did spend a short time in a behavioral health hospital after this incident. She has no known sick contacts. She does not have any other medical conditions and does not take any medications on a regular basis. She has no family history of rheumatologic or pulmonary diseases.

Vital Signs and Physical Exam

Vitals: Temperature 37°C | Pulse 90 | Respiratory rate 20 | Blood pressure 102/66 | Oxygen saturation 97% on room air

- Comfortable, no acute distress

- Mucous membranes moist, no oral ulcerations

- Normal work of breathing, diminished lung sounds on right side

- Regular rate and rhythm without murmur, normal S1/S2

- No hepatosplenomegaly, no palpable lymphadenopathy

Pertinent Labs and Imaging

| Detail | Value w/ Units | Normal Range |

| WBC | 17.71 x10(3)/mcL | 4.50-11.0 |

| HGB | 9.5 gm/dL | 12.0-16.0 |

| HCT | 29.0% | 36.0-46.0 |

| Platelet | 455 x10(3)/mcL | 150-450 |

| % Immature Gran | 2.0% | |

| % Neutrophil | 65.2% | |

| % Lymphocyte | 21.6% | |

| % Monocyte | 9.8% | |

| % Eosinophil | 1.1% | |

| % Basophil | 0.3% | |

| Sedimentation Rate | 95 mm/hr | 0-19 |

| C Reactive Prot | 18.5 mg/dL | 0.0-1.0 |

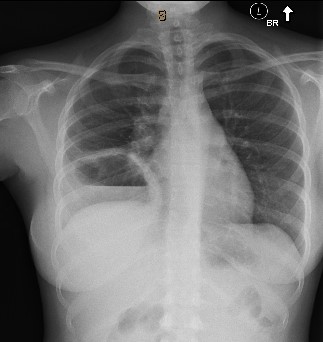

Chest radiograph from referring facility

Questions

1) Which of the following is the next best diagnostic step?

A. CT scan of chest with contrast

B. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE)

C. Doppler ultrasound of neck

D. Flexible bronchoscopy

Answer: A. CT scan of chest with contrast

This patient has a very large cavitary lesion that is concerning for an infectious process. A CT scan would provide more information on the extent of parenchymal involvement, additional areas of cavitation, and the presence of empyema. Embolic, rheumatologic and oncologic etiologies, although lower on the differential, are still possibilities and a CT scan would help with further differentiation.

A transthoracic echocardiogram and Doppler ultrasound of neck are helpful if there is a very high suspicion of an embolic source. However, the patient has no risk factors or clinical findings concerning for endocarditis or septic thrombophlebitis. A flexible bronchoscopy is generally not needed unless the patient does not respond to empiric antimicrobial therapy.

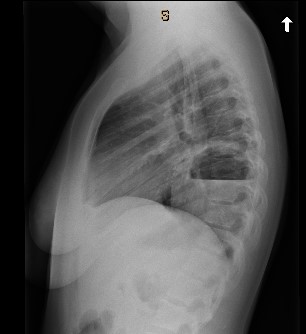

View the patient's CT scan:

2) Which of the following is most likely to reveal the diagnosis?

A. Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) bronchoscopy with lavage and biopsy

B. Sputum cultures (AFB + aerobic/anaerobic) and serum interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)

C. CT angiography and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) serologies

D. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) and blood cultures

Answer: B. Sputum cultures (AFB + aerobic/anaerobic) and serum interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)

The CT scan of the chest shows a very thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level that is most consistent with an abscess related to a complicated pneumonia. There does not appear to be any pleural involvement. Pulmonary abscesses are often polymicrobial, and additional microbiologic testing is warranted. However, anaerobic pathogens may be difficult to isolate due to overgrowth of upper airway flora and due to the fact that anaerobes generally don’t grow as well as aerobic organisms. Acid-fast smears would allow for rapid identification of tuberculosis and should always be considered with a cavitary lesion.

EBUS bronchoscopy would be appropriate if the patient was not showing clinical improvement on empiric therapy or if there was concern for malignancy and there was an appropriate window for transbronchial biopsy of a lymph node or fluid from the abscess cavity. However, this patient likely has an infectious process and has not been given a chance to improve with empiric therapy.

CT angiography plus ANCA serologies would be appropriate if there were concern for a vasculitic process. Again, the patient most likely has an infectious etiology. Vasculitis is rare in the pediatric population but could be considered if she showed no improvement or were to develop concerning symptoms of vasculitis (hemoptysis, hematuria, ulcerations, etc.).

TEE and blood cultures would be appropriate if there was concern for endocarditis. A TEE would be considered if a TTE was indeterminate or better valvular imaging was needed. This patient does not have a history of intravenous drug use, and the CT scan shows no evidence of septic emboli, making endocarditis an unlikely cause of her cavitary lesion.

Because this patient had a negative IGRA and three sputum samples that were negative for acid-fast bacilli, TB was unlikely. Her respiratory cultures (expectorated sputum) grew methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). The patient was switched from clindamycin plus ceftriaxone to ampicillin-sulbactam IV once MSSA was isolated. She remained afebrile and slowly demonstrated some clinical improvement with decreased cough.

Case Resolution

Given the preceding history and no evidence for tuberculosis, the patient likely had an aspiration event several weeks prior during her intentional ingestion of sleeping pills. The aspiration event developed into a complicated aspiration pneumonia with a lung abscess. Standard of care for lung abscess is a prolonged course of antibiotics. The patient was transitioned to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate extended release twice daily for four weeks. At the time of her three-week follow-up with the infectious diseases clinic, the chest radiograph showed some scarring but the cavitary lesion had resolved. She was instructed to complete four weeks of antibiotics as prescribed without follow-up if she continued to improve.

References:

- Desai H, Agrawal A. Pulmonary emergencies: pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, lung abscess, and empyema. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96(6):1127-1148. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42062

- DynaMed. Lung abscess. EBSCO Information Services. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/lung-abscess

- Grewal H, Evans B. Lung infections: lung biopsy, lung abscess, bronchiectasis, and empyema. In: Ziegler MM, Azizkhan RG, Allmen D, Weber TR, eds. Operative Pediatric Surgery. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill; 2014.

- Odev K, Guler I, Altinok T, Pekcan S, Batur A, Ozbiner H. Cystic and cavitary lung lesions in children: radiologic findings with pathologic correlation. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:60.